Santa vs. Jesus December 25, 2010

Posted by rationalskeptic in Christmas.Tags: Christmas, Jesus, Santa

add a comment

Today is the perfect day to re-post Santa vs. Jesus:

Christopher Hitchens and Tariq Ramadan: Is Islam A Religion of Peace? October 31, 2010

Posted by rationalskeptic in Debate.Tags: Christopher Hitchens, Debate, Islam, Religion, Tariq Ramadan

1 comment so far

Is Islam a Religion of Peace?

Christopher Hitchens and Tariq Ramadan at the 92nd Street Y

Would America Have Been Better Off Without a Reagan Presidency? October 23, 2010

Posted by rationalskeptic in Christopher Hitchens.Tags: Christopher Hitchens, Ron Reagan, Ronald Reagan

add a comment

FIGHTING WORDS

Would America Have Been Better Off Without a Reagan Presidency?

His simple-mindedness had a touch of genius to it.

By Christopher Hitchens

Posted Saturday, Feb. 5, 2011, at 7:13 AM ET

The centennial memoir of his famous parent by Ron Reagan (My Father at 100), which at first sight looks as slight as its author, is better than many press reports might suggest. For example, the younger son by no means “cashes in” on the idea that our 40th president was suffering from Alzheimer’s well before he left office; he simply adds his own private observations to what has since become perfectly obvious. A number of things apart from cognitive decay could have curtailed Reagan’s two-term reign. He might easily have died after being shot in March 1981, and indeed he was much closer to death than anybody realized at the time. He should certainly have been impeached and removed from office over the Iran-Contra racket, in which he was exposed as the president of a secret and illegal government, financed with an anti-constitutional hostage-trading and arms-dealing budget, as well as of the ostensibly legitimate one. The question that keeps recurring to me is this: Would the country and the world have been better off without his tenure of the Oval Office?

I lived in Washington for most of those eight years, and for most of them would have replied with an unhesitating “yes.” (To this day I refuse to call my local airport “Reagan,” since before the name change it was Washington National, which means, thanks very much, that it was already named for a perfectly good ex-president.) Even now I can easily remember the things that outraged me: his easy manner when lying and his sometimes breathtakingly reactionary views. These extended from the whitewashing of the SS graves at Bitburg to his opinion that Americans fighting for the Spanish Republic had been on the “wrong” side, to his discovery that apartheid South Africa had always been an ally of the United States. Then there was the abject scuttle from Lebanon and the underhanded way in which Reagan tried to blame it on the Democrats. Perhaps worst of all was an apparent fusion of two things: his indulgence of fundamentalist and millennial priestly crooks like Jerry Falwell and his seeming flippancy about nuclear war. He once maintained that intercontinental missiles could be recalled after being launched, made on-air jokes about blasting the Soviet Union, and fatuously intoned “May the Force be with you” after announcing his plan for a Strategic Defense Initiative, or “Star Wars.” The coincidence between his superstitious interest in “End Times” theology and his insouciance about nuclear matters seemed dire in the extreme. And then there was Alexander Haig as secretary of state, and Oliver North as confidant, and the wife with the astrologer …

In a bizarre way, though, his simple-mindedness turns out to have had a touch of genius to it. His grasp of physics was on a level with Hollywood beam-weapon B-movies, and how we all laughed when he told Mikhail Gorbachev that, in the event of a Martian invasion of Earth, the United States and the Soviet Union would combine to sink their differences. But he had an insight that was denied to the adherents of Mutual Assured Destruction, whose theory was rapidly coming up against diminishing returns.

Young Reagan rightly draws attention to a forgotten moment at the forgotten Republican Convention of 1976. Having only narrowly defeated him, Gerald Ford felt obliged to call on Reagan to join him on stage after accepting the nomination. Reagan took his sweet time to come to the podium, where he was already the darling of many delegates. And having done so, he said not a word in praise of Ford or his running mate, Bob Dole. Instead, he spoke about being invited to contribute something to a “time capsule” that was being readied in Los Angeles and was scheduled to be opened 100 years later. Those who opened that capsule, said Reagan, would know whether or not Armageddon had been avoided. “We live in a world in which the great powers have poised and aimed at each other horrible missiles of destruction, nuclear weapons, that can in a matter of minutes arrive at each other’s country and destroy, virtually, the civilized world we live in.”

Of course there’s an anachronistic contradiction there, in that had the weapons been used, the time capsule would never have been opened, but why quibble? It was an unusual way for the losing candidate of the right to address the faithful. A bit more than 10 years later, I was having a drink with Timothy Garton Ash in the Glasnost Café, as the coffee shop of the Marriott Hotel in Washington had been renamed while it hosted the joint press conferences of the Reagan and Gorbachev summit.* Outside, right-wing Republican nuts wearing Reagan masks were angrily flourishing umbrellas, in order to compare him to Neville Chamberlain in Munich. I said: “Well, we’ve lived to see it. The end of the goddam Cold War.” Within a much shorter time, the Berlin Wall had gone, and I could verify from the people who had written Reagan’s celebrated “tear down this wall” speech that he had insisted on the insertion of these words over the objections of many “realists.”

It was extraordinary that, in Mikhail Gorbachev, Reagan was dealing with a man who knew that the Soviet Union could not sustain the arms race and a man who was out of patience with the satraps of East Germany. To Gorbachev goes an enormous share of the credit. But if I run the thought experiment and ask myself whether Walter Mondale would have made a better interlocutor in 1987, I cannot make myself believe it. This does not involve un-saying any of the things about Reagan that his admirers would prefer us to forget. But it does acknowledge the distinction between a historic presidency and an average one. Reagan’s friend Margaret Thatcher once said that the real test of her success was the way that she had changed the politics of the Labour Party. By that standard, the legacy of Reagan in permanently altering the political landscape is with us still.

Like Slate on Facebook. Follow Slate and the Slate Foreign Desk on Twitter.

Correction, Feb. 5, 2011: This article originally placed the conversation with Timothy Garton Ash at 20 years after the 1976 Republican Convention. (Return to the corrected sentence.)

Christopher Hitchens is a columnist for Vanity Fair and the Roger S. Mertz media fellow at the Hoover Institution.

Copyright 2011 Washingtonpost.Newsweek Interactive Co. LLC

The Economic Arguement Against Psuedoscience October 21, 2010

Posted by rationalskeptic in Humor, Science.Tags: Humor, Pseudoscience

2 comments

The Economic Argument Against Pseudoscience:

Christine O’Donnell Did It Again! October 21, 2010

Posted by rationalskeptic in Constitution, Politics and Religion.Tags: Evangelical Christians, First Amendment, Oh The Stupidity

add a comment

By vorjak (@ unreasonablefaith.com)

Remember how I said that I liked the way that Christine O’Donnell would say things that were common in conservative christian circles, but uncommon in the rest of America? Well, she got in a good one during a debate with her opponent Chris Coons: “Where in the Constitution is the separation of church and state?”

This line is a staple in certain circles, and I’ve heard it any number of times on political call-in shows. But O’Donnell was foolish enough to bring it out at a law school. From The Caucus blog at the NYT:

The audience at the law school can be heard breaking out in laughter. But Ms. O’Donnell refuses to be dissuaded and pushes forward.

“Let me just clarify,” she says. “You are telling me that the separation of church and state is in the First Amendment?”

When Mr. Coons offers a shorthand of the relevant section, saying, “government shall make no establishment of religion,” Ms. O’Donnell replies, “That’s in the First Amendment?”

The worst part is that she comes across as completely clueless. That line, “Where in the Constitution &tc,” is supposed to just be the lead-in to a long diatribe about how “Separation of Church and State” is just a liberal anti-christian hoax. But when Coons repeats the First Amendment to her, she doesn’t seem to know how to proceed to the next stage.

Via Slacktivist, here’s the video. The laughter is at 2:50, then a reprise at 7:05. The post at The Caucus linked above has a condensed audio clip.

God or No God? Christopher Hitchens vs. Larry Taunton October 3, 2010

Posted by rationalskeptic in Christopher Hitchens.Tags: Christopher Hitchens, Debate, FixedPoint Foundation, Larry Taunton

2 comments

Christopher Hitchens debates Larry Taunton, Executive Director of Fixed Point Foundation.

October 19, Billings, Montana. 7pm. More (fixed-point.org)

(I am looking forward to this debate because of the opponents relatively new friendship, Taunton’s style/delivery and of course watching Hitchens debate someone he has not debated before.) Quite frankly, I wish all Christians were more like Taunton, because of his openness to dialogue and debate and honesty. Although, sometimes he seems to fall into the same trap of condescension and a coy attitude towards unbelievers, of course everyone can exhibit these bad habits, but I experience this attitude from Christians literally on a daily basis.

Here is a clip of Taunton responding to the news of Hitchens’ diagnosis:

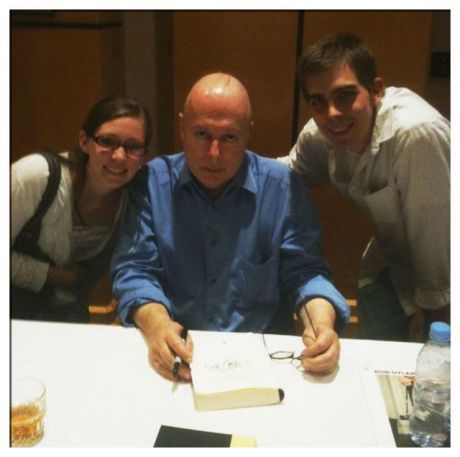

Christopher Hitchens debates David Berlinski in Birmingham, AL September 7, 2010 September 8, 2010

Posted by rationalskeptic in Christopher Hitchens.Tags: Christopher Hitchens, Debate

26 comments

Last night at the Birmingham Sheraton, my wife and I saw Christopher Hitchens debate David Berlinski, and it was an incredible evening to say the least. At one point during the debate, Hitchens asked the audience, who the Baptists of Danbury, Connecticut were in need of protection from, that prompted Jefferson to write the Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom. (the answer is the Congregationalists of Danbury, Connecticut.) Not that it was a hard question, but I was the only person in the audience to answer it correctly, i had to mention that.

Hitchens really mopped the floor with Berlinski, it was almost too easy for Hitchens in this debate, Berlinski was very dull and seemed to just be annoyed by the whole new atheist “phenomenon.”

Afterwards, Hitchens signed books and and sat for pictures, he is the nicest and most humble public intellectual I have ever had the honor to meet.

(I’ll post a more thorough review soon)

Unanswerable Prayers (Christopher Hitchens in Vanity Fair October 2010) September 6, 2010

Posted by rationalskeptic in Uncategorized.2 comments

October 2010

HE OF LITTLE FAITH

The author at home in Washington, D.C.

When I described the tumor in my esophagus as a “blind, emotionless alien,” I suppose that even I couldn’t help awarding it some of the qualities of a living thing. This at least I know to be a mistake: an instance of the “pathetic fallacy” (angry cloud, proud mountain, presumptuous little Beaujolais) by which we ascribe animate qualities to inanimate phenomena. To exist, a cancer needs a living organism, but it cannot ever become a living organism. Its whole malice—there I go again—lies in the fact that the “best” it can do is to die with its host. Either that or its host will find the measures with which to extirpate and outlive it.

But, as I knew before I became ill, there are some people for whom this explanation is unsatisfying. To them, a rodent carcinoma really is a dedicated, conscious agent—a slow-acting suicide-murderer—on a consecrated mission from heaven. You haven’t lived, if I can put it like this, until you have read contributions such as this on the Web sites of the faithful:

Who else feels Christopher Hitchens getting terminal throat cancer [sic] was God’s revenge for him using his voice to blaspheme him? Atheists like to ignore FACTS. They like to act like everything is a “coincidence”. Really? It’s just a “coincidence” [that] out of any part of his body, Christopher Hitchens got cancer in the one part of his body he used for blasphemy? Yea, keep believing that Atheists. He’s going to writhe in agony and pain and wither away to nothing and then die a horrible agonizing death, and THEN comes the real fun, when he’s sent to HELLFIRE forever to be tortured and set afire.

There are numerous passages in holy scripture and religious tradition that for centuries made this kind of gloating into a mainstream belief. Long before it concerned me particularly I had understood the obvious objections. First, which mere primate is so damn sure that he can know the mind of god? Second, would this anonymous author want his views to be read by my unoffending children, who are also being given a hard time in their way, and by the same god? Third, why not a thunderbolt for yours truly, or something similarly awe-inspiring? The vengeful deity has a sadly depleted arsenal if all he can think of is exactly the cancer that my age and former “lifestyle” would suggest that I got. Fourth, why cancer at all? Almost all men get cancer of the prostate if they live long enough: it’s an undignified thing but quite evenly distributed among saints and sinners, believers and unbelievers. If you maintain that god awards the appropriate cancers, you must also account for the numbers of infants who contract leukemia. Devout persons have died young and in pain. Bertrand Russell and Voltaire, by contrast, remained spry until the end, as many psychopathic criminals and tyrants have also done. These visitations, then, seem awfully random. While my so far uncancerous throat, let me rush to assure my Christian correspondent above, is not at all the only organ with which I have blasphemed …And even if my voice goes before I do, I shall continue to write polemics against religious delusions, at least until it’s hello darkness my old friend. In which case, why not cancer of the brain? As a terrified, half-aware imbecile, I might even scream for a priest at the close of business, though I hereby state while I am still lucid that the entity thus humiliating itself would not in fact be “me.” (Bear this in mind, in case of any later rumors or fabrications.)

The absorbing fact about being mortally sick is that you spend a good deal of time preparing yourself to die with some modicum of stoicism (and provision for loved ones), while being simultaneously and highly interested in the business of survival. This is a distinctly bizarre way of “living”—lawyers in the morning and doctors in the afternoon—and means that one has to exist even more than usual in a double frame of mind. The same is true, it seems, of those who pray for me. And most of these are just as “religious” as the chap who wants me to be tortured in the here and now—which I will be even if I eventually recover—and then tortured forever into the bargain if I don’t recover or, presumably and ultimately, even if I do.

Of the astonishing and flattering number of people who wrote to me when I fell so ill, very few failed to say one of two things. Either they assured me that they wouldn’t offend me by offering prayers or they tenderly insisted that they would pray anyway. Devotional Web sites consecrated special space to the question. (If you should read this in time, by all means keep in mind that September 20 has already been designated “Everybody Pray for Hitchens Day.”) Pat Archbold, at the National Catholic Register, and Deacon Greg Kandra were among the Roman Catholics who thought me a worthy object of prayer. Rabbi David Wolpe, author of Why Faith Matters and the leader of a major congregation in Los Angeles, said the same. He has been a debating partner of mine, as have several Protestant evangelical conservatives like Pastor Douglas Wilson of the New St. Andrews College and Larry Taunton of the Fixed Point Foundation in Birmingham, Alabama. Both wrote to say that their assemblies were praying for me. And it was to them that it first occurred to me to write back, asking: Praying for what?

As with many of the Catholics who essentially pray for me to see the light as much as to get better, they were very honest. Salvation was the main point. “We are, to be sure, concerned for your health, too, but that is a very secondary consideration. ‘For what shall it profit a man if he gains the whole world and forfeits his own soul?’ [Matthew 16:26.]” That was Larry Taunton. Pastor Wilson responded that when he heard the news he prayed for three things: that I would fight off the disease, that I would make myself right with eternity, and that the process would bring the two of us back into contact. He couldn’t resist adding rather puckishly that the third prayer had already been answered…

So these are some quite reputable Catholics, Jews, and Protestants who think that I might in some sense of the word be worth saving. The Muslim faction has been quieter. An Iranian friend has asked for prayer to be said for me at the grave of Omar Khayyám, supreme poet of Persian freethinkers. The YouTube video announcing the day of intercession for me is accompanied by the song “I Think I See the Light,” performed by the same Cat Stevens who as “Yusuf Islam” once endorsed the hysterical Iranian theocratic call to murder my friend Salman Rushdie. (The banal lyrics of his pseudo-uplifting song, by the way, appear to be addressed to a chick.) And this apparent ecumenism has other contradictions, too. If I were to announce that I had suddenly converted to Catholicism, I know that Larry Taunton and Douglas Wilson would feel I had fallen into grievous error. On the other hand, if I were to join either of their Protestant evangelical groups, the followers of Rome would not think my soul was much safer than it is now, while a late-in-life decision to adhere to Judaism or Islam would inevitably lose me many prayers from both factions. I sympathize afresh with the mighty Voltaire, who, when badgered on his deathbed and urged to renounce the devil, murmured that this was no time to be making enemies.

The Danish physicist and Nobelist Niels Bohr once hung a horseshoe over his doorway. Appalled friends exclaimed that surely he didn’t put any trust in such pathetic superstition. “No, I don’t,” he replied with composure, “but apparently it works whether you believe in it or not.” That might be the safest conclusion. The most comprehensive investigation of the subject ever conducted—the “Study of the Therapeutic Effects of Intercessory Prayer,” of 2006—could find no correlation at all between the number and regularity of prayers offered and the likelihood that the person being prayed for would have improved chances. But it did find a small but interesting negative correlation, in that some patients suffered slight additional woe when they failed to manifest any improvement. They felt that they had disappointed their devoted supporters. And morale is another unquantifiable factor in survival. I now understand this better than I did when I first read it. An enormous number of secular and atheist friends have told me encouraging and flattering things like: “If anyone can beat this, you can”; “Cancer has no chance against someone like you”; “We know you can vanquish this.” On bad days, and even on better ones, such exhortations can have a vaguely depressing effect. If I check out, I’ll be letting all these comrades down. A different secular problem also occurs to me: what if I pulled through and the pious faction contentedly claimed that their prayers had been answered? That would somehow be irritating.

I have saved the best of the faithful until the last. Dr. Francis Collins is one of the greatest living Americans. He is the man who brought the Human Genome Project to completion, ahead of time and under budget, and who now directs the National Institutes of Health. In his work on the genetic origins of disorder, he helped decode the “misprints” that cause such calamities as cystic fibrosis and Huntington’s disease. He is working now on the amazing healing properties that are latent in stem cells and in “targeted” gene-based treatments. This great humanitarian is also a devotee of the work of C. S. Lewis and in his book The Language of God has set out the case for making science compatible with faith. (This small volume contains an admirably terse chapter informing fundamentalists that the argument about evolution is over, mainly because there is no argument.) I know Francis, too, from various public and private debates over religion. He has been kind enough to visit me in his own time and to discuss all sorts of novel treatments, only recently even imaginable, that might apply to my case. And let me put it this way: he hasn’t suggested prayer, and I in turn haven’t teased him about The Screwtape Letters. So those who want me to die in agony are really praying that the efforts of our most selfless Christian physician be thwarted. Who is Dr. Collins to interfere with the divine design? By a similar twist, those who want me to burn in hell are also mocking those kind religious folk who do not find me unsalvageably evil. I leave these paradoxes to those, friends and enemies, who still venerate the supernatural.

Pursuing the prayer thread through the labyrinth of the Web, I eventually found a bizarre “Place Bets” video. This invites potential punters to put money on whether I will repudiate my atheism and embrace religion by a certain date or continue to affirm unbelief and take the hellish consequences. This isn’t, perhaps, as cheap or as nasty as it may sound. One of Christianity’s most cerebral defenders, Blaise Pascal, reduced the essentials to a wager as far back as the 17th century. Put your faith in the almighty, he proposed, and you stand to gain everything. Decline the heavenly offer and you lose everything if the coin falls the other way. (Some philosophers also call this Pascal’s Gambit.)

Ingenious though the full reasoning of his essay may be—he was one of the founders of probability theory—Pascal assumes both a cynical god and an abjectly opportunist human being. Suppose I ditch the principles I have held for a lifetime, in the hope of gaining favor at the last minute? I hope and trust that no serious person would be at all impressed by such a hucksterish choice. Meanwhile, the god who would reward cowardice and dishonesty and punish irreconcilable doubt is among the many gods in which (whom?) I do not believe. I don’t mean to be churlish about any kind intentions, but when September 20 comes, please do not trouble deaf heaven with your bootless cries. Unless, of course, it makes you feel better.

Read More http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/features/2010/10/hitchens-201010?printable=true#ixzz0ylORWpUz

Hitch-22 by Christopher Hitchens June 20, 2010

Posted by rationalskeptic in Christopher Hitchens.Tags: Christopher Hitchens, Hitch-22

4 comments

This is an excert from Christopher Hitchens’ new memoir Hitch-22 (originally posted at Slate.com):

Hitch-22

A short footnote on the grape and the grain.

By Christopher Hitchens

Updated Monday, June 7, 2010, at 7:20 AM ET

An ancient piece of Judaic commentary holds that the liver is the organ that best represents the relationship between parents and child: it is the heaviest of all the viscera and accordingly the most appropriate bit of one’s guts. Only two of the six hundred and thirteen Jewish commandments, or prohibitions, offer any reward for compliance and both are parental: the first is in the original Decalogue when those who “honor thy father and thy mother” are assured that this will increase their days in the promised or stolen Canaanite land that is about to be given them, and the second involves some convoluted piece of quasi-reasoning whereby a bird’s egg can be taken by a hungry Jew as long as the poor mother bird isn’t there to witness the depredation. How to discern whether it’s a mother or father bird is not confided by the sages.

Commander Eric Ernest Hitchens of the Royal Navy (my middle name is Eric and I have sometimes idly wondered how things might have been different if either of us had been called Ernest) was a man of relatively few words, would have had little patience for Talmudic convolutions, and was not one of those whom nature had designed to be a nest-builder. But his liver—to borrow a phrase from Gore Vidal—was “that of a hero,” and I must have inherited from him my fondness, if not my tolerance, for strong waters. I can remember perhaps three or four things of the rather laconic and diffident sort that he said to me. One—also biblically derived—was that my early socialist conviction was “founded on sand.” Another was that while one ought to beware of women with thin lips (this was the nearest we ever approached to a male-on-male conversation), those with widely spaced eyes were to be sought out and appreciated: excellent advice both times and no doubt dearly bought. Out of nowhere in particular, but on some unusually bleak West Country day he pronounced: “I sometimes think that the Gulf Stream is beginning to weaken,” thereby anticipating either the warming or else the cooling that seemingly awaits us all. When my firstborn child, his first grandson, arrived, I got a one-line card: “glad it’s a boy.” Perhaps you are by now getting an impression. But the remark that most summed him up was the flat statement that the war of 1939 to 1945 had been “the only time when I really felt I knew what I was doing.”

This, as I was made to appreciate while growing up myself, had actually been the testament of a British generation. Born in the early years of the century, afflicted by slump and Depression after the First World War in which their fathers had fought, then flung back into combat against German imperialism in their maturity, starting to get married and to have children in the bleak austerity that succeeded victory in 1945, they all wondered quite where the years of their youth and strength had gone, and saw only more decades of struggle and hardship still to come before the exigencies of retirement. As Bertie Wooster once phrased it, they experienced some difficulty in detecting the bluebird.

My entire boyhood was overshadowed by two great subjects, one of them majestic and the other rather less so. The first was the recent (and terribly costly) victory of Britain over the forces of Nazism. The second was the ongoing (and consequent) evacuation by British forces of bases and colonies that we could no longer afford to maintain. This epic and its closure were inscribed in the very scenery around me: Portsmouth and Plymouth had both been savagely blitzed and the scars were still palpable. The term “bomb-site” was a familiar one, used to describe a blackened gap in a street or the empty place where an office or pub used to stand. More than this, though, the drama was inscribed in the circumambient culture. Until I was about thirteen, I thought that all films and all television programs were about the Second World War, with a strong emphasis on the role played in that war by the Royal Navy. I saw Jack Hawkins with his binoculars on the icy bridge in The Cruel Sea: the movie version of a heart-stopping novel about the Battle of the Atlantic by Nicholas Monsarrat that by then I knew almost by heart. The Commander, who had seen action on his ship HMS Jamaica in almost every maritime theater from the Mediterranean to the Pacific, had had an especially arduous and bitter time, escorting convoys to Russia “over the hump” of Scandinavia to Murmansk and Archangel at a time when the Nazis controlled much of the coast and the air, and on the day after Christmas 1943 (“Boxing Day” as the English call it) proudly participating as the Jamaica pressed home for the kill and fired torpedoes through the hull of one of Hitler’s most dangerous warships, the Scharnhorst. Sending a Nazi convoy raider to the bottom is a better day’s work than any I have ever done, and every year on the anniversary the Commander would allow himself one extra tot of Christmas cheer, or possibly two, which nobody begrudged him. (To this day, I observe the occasion myself.)

But he would then become glum, because he had most decidedly not taken the King’s Commission in order to end up running guns to Joseph Stalin (he had loathed the glum, graceless reception he got when his ship docked under the gaze of the Red Navy) and because almost everything since that great Boxing Day had been headed downhill. The Empire and the Navy were being wound up fast, the colors were being struck from Malaya in the East to Cyprus and Malta nearer home, the Senior Service itself was being cut to the bone. When I was born in Portsmouth, my father was onboard a ship called the Warrior, anchored in a harbor that had once seen scores of aircraft carriers and great gray battleships pass in review. In Malta there had still been a shimmer or scintilla of greatness to the Navy, but by the time I was old enough to take notice the Commander was putting on his uniform only to go to a “stone frigate”: a non-seagoing dockside office in Plymouth where they calculated things in ledgers. Every morning on the BBC until I was six I would hear the newscaster utter the name “Sir Winston Churchill,” who was then prime minister. There came the day when this stopped, and my childish ears received the strange name “Sir Anthony Eden,” who had finally succeeded the old lion. Within a year or so, Eden had tried to emulate Churchill by invading Egypt at Suez, and pretending that Britain could simultaneously do without the U.N. and the United States. International and American revenge was swift, and from then on the atmosphere can’t even be described as a “long, withdrawing roar,” since the tide of empire and dominion merely and sadly ebbed.

“We won the war—or did we?” This remark, often accompanied by a meaning and shooting glance and an air of significance, was a staple of conversation between my father and his rather few friends as the decanter went round. Later in life, I am very sorry to say, it helped me to understand the “stab in the back” mentality that had infected so much of German opinion after 1918. You might call it the politics of resentment. These men had borne the heat and burden of the day, but now the only chatter in the press was of cheap and flashy success in commerce; now the colonies and bases were being mortgaged to the Americans (who, as we were invariably told, had come almost lethargically late to the struggle against the Axis); now there were ridiculous, posturing, self-inflated leaders like Kenyatta and Makarios and Nkrumah where only very recently the Union Jack had guaranteed prosperity under law. This grievance was very deeply felt but was also, except in the company of fellow sufferers, rather repressed. The worst thing the Navy did to the Commander was to retire him against his will sometime after Suez, and then and only then to raise the promised pay and pension of those officers who would later join up. This betrayal by the Admiralty was a never-ending source of upset and rancor: the more wartime service and action you had seen, the less of a pension you received. The Commander would write letters to Navy ministers and members of Parliament, and he even joined an association of “on the beach” ex-officers like himself. But one day when, tiring of his plaintiveness, I told him that nothing would change until he and his comrades marched in a phalanx to Buckingham Palace and handed back their uniforms and swords and scabbards and medals, he was quite shocked. “Oh,” he responded. “We couldn’t think of doing that.” Thus did I begin to see, or thought I began to see, how the British Conservatives kept the fierce, irrational loyalty of those whom they exploited. “He’s a Tory,” I was much later to hear of some dogged loyalist, “but he’s got nothing to be Tory about.” My thoughts immediately flew to my father, whose own devoted and brave loyalism had been estimated so cheaply by what I was by then calling the ruling class.

He was quite a small man and, when he took off his uniform (or had it taken away from him) and went to work as a bookkeeper, looked very slightly shrunken. For as long as he could, he took jobs that kept him near the sea, especially near the Hampshire-Sussex coast. He would work for a boatbuilder here, a speedboat-manufacturer there. We finally drifted inland, nearer to the center of my mother’s beloved Oxford, where there was a boys’ prep school that needed an accountant, and he seized the chance to acquire a dog. I hadn’t realized until then quite how much he preferred the predictability and loyalty of animals to the vagaries and frailties of human beings. Late in life the landlords of the apartment building where he lived were to tell him that he couldn’t keep his red-setter/retriever mix, a lovely animal named Becket. The now-beached Commander couldn’t afford to move house again, so instead of protesting, he meekly gave the dog away. But not before mooting with me a plan to establish Becket somewhere else, “so that I could go and visit him from time to time.” Again I had the experience of a moment of piercing pity, of the sort I could only now imagine feeling for a child of mine whom it was beyond my power to help.

I do have a heroic memory of him from my boyhood, and it happens to concern water. We were at a swimming-pool party, held at the local golf and country club that was almost but not quite out of our social orbit, when I heard a splash and saw the Commander fully clothed in the shallow end, pipe still clamped in his mouth. I remember hoping that he had not fallen in, in front of all these people, because of the gin. Then I saw that he was holding a little girl in his arms. She had been drowning, quietly, just outside her depth, until someone had squealed an alarm and my father had been the speediest man to act. I remember two things about the aftermath. The first was the Commander’s “no fuss; anyone would have done it” attitude to those who slapped him on the back in admiration. That was absolutely in character, and to be expected. But the second was the glare of undisguised rage and hatred from the little girl’s father, who should have been paying attention and who had instead been quaffing and laughing with his pals. That hateful look taught me a lot about human nature in a short time.

Otherwise I am rather barren of paternal recollections, and shall have to settle for the memory of a few walks, and for the strange cult of golf. Seafarer though he was, my father loved the downlands of Hampshire and Sussex and later Oxfordshire and could stride along with his trusty stick, pointing out here a steading and there a ridgeway. He was a Saxon in his own way, and still had the attitude, now almost extinct, that there had been such a thing as “the Norman yoke” imposed upon this ancient landscape and people. A favorite joke on his side of the family concerned the Hampshire yeoman in dispute with his squire. “I suppose you know,” observes the squire loftily, “that my ancestors came over with William the Conqueror.” “Yes,” responds the yeoman. “We were waiting for you.” (In an alternative version once offered by the rogue Marxist Welshman Raymond Williams, the yeoman tries to be witty and says: “Oh yes, and how are you liking it over here?”) I mention this because a certain kind of British conservatism is quite closely connected with this folk memory of populism and ethnicity, and because it became important for me to comprehend this later on.

The golf game must have taken place when I was about thirteen. I had taken up the sport, and even got myself a few clubs, with the idea that I ought to have something in common with my reticent old man, who loved golf and treasured a pewter mug he had once won in a Navy tournament held on the deck of an aircraft carrier. My effort paid off, if only once. We had a round of nine holes that somehow went well for both of us, and then he treated me to a heavy “tea” in the clubhouse where, if nothing much got said, there was no tension or awkwardness, either. It was the closest I ever came, or felt, to him. There was a very soft and beautiful dusk, I remember, as we drove slowly and quietly home through the purple-and-yellow gorse of the moors.

Buy Hitch-22.

Like Slate on Facebook. Follow Slate and the Slate Foreign Desk on Twitter.

——————————————————————————–

From: Christopher Hitchens

Subject: Fragments From an Education

Posted Thursday, June 3, 2010, at 6:49 PM ET

——————————————————————————–

I often have difficulty convincing my graduate students that I really did go off to prep school at the age of eight, from station platforms begrimed with coal dust and echoing to the mounting “whomp, whomp, woof, woof” of the pistons beginning to turn, as my own “trunk” and “tuck box” were loaded into a “luggage car.” Not only that, but that I wore corduroy shorts in all weathers, blazers with a school crest on Sundays, slept in a dormitory with open windows, began every day with a cold bath (followed by the declension of Latin irregular verbs), wolfed lumpy porridge for breakfast, attended compulsory divine service every morning and evening, and kept a diary in which—in a special code—I recorded the number of times when I was left alone with a grown-up man, who was perhaps four times my weight and five times my age, and bent over to be thrashed with a cane.

The strange thing, or so I now think, was the way in which it didn’t feel all that strange. The fictions and cartoons of Nigel Molesworth, of Paul Pennyfeather in Waugh’s Decline and Fall, and numberless other chapters of English literary folklore have somehow made all this mania and ritual appear “normal,” even praiseworthy. Did we suspect our schoolmasters—not to mention their weirdly etiolated female companions or “wives,” when they had any—of being in any way “odd,” not to say queer? We had scarcely the equipment with which to express the idea, and anyway what would this awful thought make of our parents, who were paying—as we were so often reminded—a princely sum for our privileged existences? The word “privilege” was indeed employed without stint. Yes, I think that must have been it. If we had not been certain that we were better off than the oafs and jerks who lived on housing estates and went to state-run day schools, we might have asked more questions about being robbed of all privacy, encouraged to inform on one another, taught how to fawn upon authority and turn upon the vulnerable outsider, and subjected at all times to rules which it was not always possible to understand, let alone to obey.

I think it was that last point which impressed itself upon me most, and which made me shudder with recognition when I read Auden’s otherwise overwrought comparison of the English boarding school to a totalitarian regime. The conventional word that is employed to describe tyranny is “systematic.” The true essence of a dictatorship is in fact not its regularity but its unpredictability and caprice; those who live under it must never be able to relax, must never be quite sure if they have followed the rules correctly or not. (The only rule of thumb was: whatever is not compulsory is forbidden.) Thus, the ruled can always be found to be in the wrong. The ability to run such a “system” is among the greatest pleasures of arbitrary authority, and I count myself lucky, if that’s the word, to have worked this out by the time I was ten. Later in life I came up with the term “micro-megalomaniac” to describe those who are content to maintain absolute domination of a small sphere. I know what the germ of the idea was, all right. “Hitchens, take that look off your face!” Near-instant panic. I hadn’t realized I was wearing a “look.” (Face-crime!) “Hitchens, report yourself at once to the study!” “Report myself for what, sir?” “Don’t make it worse for yourself, Hitchens, you know perfectly well.” But I didn’t. And then: “Hitchens, it’s not just that you have let the whole school down. You have let yourself down.” To myself I was frantically muttering: Now what? It turned out to be some dormitory sex-game from which—though the fools in charge didn’t know it—I had in fact been excluded. But a protestation of my innocence would have been, as in any inquisition, an additional proof of guilt.

There were other manifestations, too. There was nowhere to hide. The lavatory doors sometimes had no bolts. One was always subject to invigilation, waking and sleeping. Collective punishment was something I learned about swiftly: “Until the offender confesses in public,” a giant voice would intone, “all your ‘privileges’ will be withdrawn.” There were curfews, where we were kept at our desks or in our dormitories under a cloud of threats while officialdom prowled the corridors in search of unspecified crimes and criminals. Again I stress the matter of sheer scale: the teachers were enormous compared to us and this lent a Brobdingnagian aspect to the scene. In seeming contrast, but in fact as reinforcement, there would be long and “jolly” periods where masters and boys would join in scenes of compulsory enthusiasm—usually over the achievements of a sports team—and would celebrate great moments of victory over lesser and smaller schools. I remember years later reading about Stalin that the intimates of his inner circle were always at their most nervous when he was in a “good” mood, and understanding instantly what was meant by that.

And yet it still wasn’t fascism, and the men and women who ran this bizarre microcosm were dedicated in their own weird way. The school, Mount House, was on the edge of Dartmoor—the site of the famously grim prison in Waugh’s Decline and Fall—and haggard, despairing escaped convicts were more than once recaptured after hiding in the sheds on our cricket grounds. Yet the natural beauty of the region was astonishing, and our teachers were on hand all day and at weekends, many of them conveying their enthusiasm for birds and animals and trees. We were all of us compelled to sit through lessons in the sinister fairy tales of Christianity as well, and nature was sometimes enlisted as illustrating god’s design, but I can’t pretend that I hated singing the hymns or learning the psalms, and I enjoyed being in the choir and was honored when asked to read from the lectern on Sundays. In fact, as you have perhaps guessed, I was getting an early training in the idea that life meant keeping two separate and distinct sets of books. If my parents knew what really went on at the school, I used to think (not being the first little boy to imagine that my main job was that of protecting parental innocence), they would faint from the shock. So I would be staunch and defend them from the knowledge. Meanwhile, and speaking of books, the school possessed its very own library, and several of the masters had private collections of their own, to which one might be admitted (not always without risk to these men’s immortal souls) as a great treat.

This often feels as if it happened to somebody else yet I can be sure it did not because I can recall the element of sadomasochism so well. Awareness of this is no doubt innate in all of us, and I suppose a case could be made for teaching it to children as part of “sex education” or the facts of life, but I had to sit in a freezing classroom at first light, at a tender age, and hear my silver-haired Latin teacher Mr. Witherington approach the verge of tears as he digressed from the study of Caesar and Tacitus and told us with an awful catch in his voice of the way in which he had been flogged at Eastbourne School. And that same brutish academy, we thought as we squirmed our tiny rears on the wooden benches, was one of those to which we were supposed to aspire. I think I wish I had not been introduced so early to the connection between obscure sexual excitement and the infliction—or the reception—of pain.

Again come the two sets of books: I would escape to the library and lose myself in the adventure stories of John Buchan and “Sapper” and G.A. Henty and Percy Westerman, and acquaint myself with imperial and military values just as, unknown to me in the England of the late 1950s that lay outside the school’s boundary, these were going straight out of style. Meanwhile and on the other side of the ledger, I would tell myself that I wasn’t really part of the hierarchy of cruelty, either as bully or victim. I wasn’t any use at sports, I didn’t have the kind of “keenness” that made one even a junior prefect, but on the other hand I did need to protect myself from being a mere weed and weakling and kick-bag. Sometimes there was a fatso or freak toward whom I could divert the attention of the mob, but I can honestly claim to have become ashamed of this tactic. There came a day when, without exactly realizing it in a fully conscious manner, I understood that words could function as weapons. I don’t remember all the offenses and hurts that had been inflicted on me, but I do recollect exactly what I said as I whirled on my playground tormentor, an especially vile boy named Welchman who was a snitch and a stoolpigeon as well as the embodiment of the (not invariably reliable) maxim that all bullies are cowards at heart. “You,” I said in fairly level but loud tones through my split lips, “are a liar, a bully, a coward, and a thief.” It was amazing to see the way in which this lummox fell back, his face filling with alarm. It was also quite something to see the tide of playground public opinion turn so suddenly against him.

Looking back, it is the masochistic element that impresses me more than the sadistic one. It’s relatively easy to see why people want to exert power over others, but what fascinated me was the way in which the victims colluded in the business. Bullies would acquire a personal squad of toadies with impressive speed and ease. The more tyrannical the schoolmaster, the more those who lived in fear of him would rush to placate him and to anticipate his moods. Small boys who were ill-favored, or “out of favor” with authority, would swiftly attract the derision and contempt of the majority as well. I still writhe when I think how little I did to oppose this. My tongue sharpened itself mainly in my own defense.

Hugh Wortham, my huge and dominating headmaster and introducer to the dark arts of corporal punishment, was a lifelong bachelor, but some of the local mothers found him handsome, and Yvonne gaily said that he put her in mind of Rex Harrison. His huge, brawny, furry arms and his immense horseshoes of teeth made him seem almost gorilla-like to me and a bold contrast to the rather slight figure of the Commander. His rages would shake the windows and make small boys turn white: his “good moods” were a hell to endure and a challenge to manipulate. Heaven knows what he’d been through sexually: he himself didn’t stoop to “fiddling” with any of us but if you were occasionally favored, as I occasionally was, you would be given a copy of David Blaize or one of the Jeremy novels and asked if you’d care to read it “in your free time.” Though I didn’t have the vocabulary for this in those days, I now know quite a lot about E.F. Benson and Hugh Walpole and I sensed even then that this was the world of the smoldering and yearning and repressed adult homosexual, fixated on his own schooldays and probably most attracted to those who are themselves blithely unaware of the intensity of the attention.

There were also some masters, twitchy and sad and at the end of their tethers and the close of their careers, who by the same herd instinct we knew to be fair game. Poor old Mr. Robertson—”Rubberguts,” with his decrepit Austin car and his equally decrepit wife Lydia—could not keep order and made the fatal mistake of trying to curry favor with the boys by little acts of kindness and bribery with sweets. He was childless and pathetic and he taught the unmanly subject of geography, and we somehow knew that the real authorities in the school didn’t respect him either, so we felt free to make his life a misery. There was more satisfaction to be had in teasing and torturing a feeble member of the Establishment than there was in cornering some hapless and pustular bedwetter of our own cohort. Rubberguts eventually left the school and for all I know died in poverty in some seaside boardinghouse, but before we broke him the poor childless chap swooped on me one day in the changing rooms, caught me under the armpits, held me up and gave me, or to be exact my forehead, the most chaste possible kiss. Then he put me down and silently, sadly mooched away. At first I thought I had a good tale to share with my fellow gloating little beasts, but then I found myself admitting that there had been nothing so creepy about it, merely something melancholy, and I never said a word to a soul. It is strange how the boundary between the knowing and the innocent is subconsciously patrolled: one may be apparently quite “wised up” while being in reality quite naïve, or entirely unaware of the grosser aspects of existence while yet possessing some intuition of what lies on the other side of the adult veil. I couldn’t make this encounter seem dirty while there were boys more advanced than myself who could make even the word “clean” sound suggestive. I suspected that they sometimes pretended to know more than they really did.

And this is partly why I can’t entirely second or echo his own great memoir of prep-school misery. For me, the experience of being sent away at a tender age was, at any cost, finally an emancipating one. I knew I hadn’t been dispatched to boarding school to get me out of the way (an assurance that I don’t think the young Orwell shared). I knew it was my only eventual meal ticket for a decent university: that undiscovered country to which no Hitchens had yet traveled. I knew that I owed my parents the repayment of a debt. True, I did get pushed around and unfairly punished and introduced too soon to some distressing facts of existence, but I would not have preferred to stay at home or to have been sheltered from these experiences, and it was probably good for me to be deprived of my adoring mother and taught—I can still remember the phrase—that I wasn’t by any means “the only pebble on the beach.” Why, I once inquired, was the school boxing tournament into which I had been entered against my will called “The Ninety Percent”? “Because, Hitchens, the fight involves only ten percent skill and ninety percent guts.” This seemed even then like a parody of a Tom Brown story, and I had the socks knocked off me in the ring, but why do I remember it after half a century? The school motto was Ut Prosim (“That I May Be Useful”), and when one has joined in the singing of “I Vow to Thee My Country”—especially on 11 November by the war memorial—or “The Day Thou Gavest, Lord, Is Ended” (“To sing is to pray twice,” as St. Augustine put it) then one may in fact be very slightly better equipped to face that Japanese jail or Iraqi checkpoint.

I have just looked up the gleaming new website of Mount House, and realized that if I have set all this down in my turn, it is because I was among the last generation to go through the “old school” version of Englishness. The site speaks enthusiastically of the number of girls being educated at the establishment (good grief!), of the availability of vegetarian diets and caterings for other “special needs,” and of its sensitivity to various sorts of “learning disability.” Now I cannot say I am completely sorry to think that there will be no more “eat that mutton, Hitchens” or “bend over that chair, Hitchens,” or “shall we call him Christine, boys, he’s so feeble?” but something in me hopes that it hasn’t all become positive reinforcement, with high marks constantly awarded for mere self-esteem.

Buy Hitch-22.

Like Slate on Facebook. Follow Slate and the Slate Foreign Desk on Twitter.

——————————————————————————–

From: Christopher Hitchens

Subject: A Short Footnote on the Grape and the Grain

Posted Sunday, June 6, 2010, at 6:03 AM ET

——————————————————————————–

In the continuing effort to gain some idea of how one appears to other people, nothing is more useful than exposing oneself to an audience of strangers in a bookstore or a lecture hall. Very often, for example, sitting anxiously in the front row are motherly-looking ladies who, when they later come to have their books inscribed, will say such reassuring things as: “It’s so nice to meet you in person: I had the impression that you were so angry and maybe unhappy.” I hadn’t been at all aware of creating this effect. (One of them, asking me to sign her copy of my Letters to a Young Contrarian, said to me wistfully: “I bought a copy of this to give to my son, hoping he’d become a contrarian, but he refused.” Adorno would have appreciated the paradox.)

More affecting still is the anxious, considerate way that my hosts greet me, sometimes even at the airport, with a large bottle of Johnnie Walker Black Label. It’s almost as if they feel that they must propitiate the demon that I bring along with me. Interviewers arriving at my apartment frequently do the same, as if appeasing the insatiable. I don’t want to say anything that will put even a small dent into this happy practice, but I do feel that I owe a few words. There was a time when I could reckon to outperform all but the most hardened imbibers, but I now drink relatively carefully. This ought to be obvious by induction: on average I produce at least a thousand words of printable copy every day, and sometimes more. I have never missed a deadline. I give a class or a lecture or a seminar perhaps four times a month and have never been late for an engagement or shown up the worse for wear. My boyish visage and my mellifluous tones are fairly regularly to be seen and heard on TV and radio, and nothing will amplify the slightest slur more than the studio microphone. (I think I did once appear on the BBC when fractionally whiffled, but those who asked me about it later were not sure whether I was not, a few days after September 11, a bit angry as well as a bit tired.) Anyway, it should be obvious that I couldn’t do all of this if I was what the English so bluntly call a “piss-artist.”

It’s the professional deformation of many writers, and has ruined not a few. (I remember Kingsley Amis, himself no slouch, saying that he could tell on what page of the novel Paul Scott had reached for the bottle and thrown caution to the winds.) I work at home, where there is indeed a bar-room, and can suit myself. But I don’t. At about half past midday, a decent slug of Mr. Walker’s amber restorative, cut with Perrier water (an ideal delivery system) and no ice. At luncheon, perhaps half a bottle of red wine: not always more but never less. Then back to the desk, and ready to repeat the treatment at the evening meal. No “after dinner drinks”—most especially nothing sweet and never, ever any brandy. “Nightcaps” depend on how well the day went, but always the mixture as before. No mixing: no messing around with a gin here and a vodka there.

Alcohol makes other people less tedious, and food less bland, and can help provide what the Greeks called entheos, or the slight buzz of inspiration when reading or writing. The only worthwhile miracle in the New Testament—the transmutation of water into wine during the wedding at Cana—is a tribute to the persistence of Hellenism in an otherwise austere Judaea. The same applies to the Seder at Passover, which is obviously modeled on the Platonic symposium: questions are asked (especially of the young) while wine is circulated. No better form of sodality has ever been devised: at Oxford one was positively expected to take wine during tutorials. The tongue must be untied. It’s not a coincidence that Omar Khayyam, rebuking and ridiculing the stone-faced Iranian mullahs of his time, pointed to the value of the grape as a mockery of their joyless and sterile regime. Visiting today’s Iran, I was delighted to find that citizens made a point of defying the clerical ban on booze, keeping it in their homes for visitors even if they didn’t particularly take to it themselves, and bootlegging it with great brio and ingenuity. These small revolutions affirm the human.

At the wild Saturnalia that climaxes John Steinbeck’s Tortilla Flat, the charismatic Danny manages to lay so many women that, afterward, even the females who didn’t receive his attentions prefer to claim, rather than appear to have been overlooked, that they were included, too. I can’t make any comparable boast but quite often I get second-hand reports about people who claim to have spent evenings in my company that belong to song, story, and legend when it comes to the Dionysian. I once paid a visit to the grotesque holding-pen that the United States government maintains at Guantánamo Bay in Cuba. There wasn’t an unsupervised moment on the whole trip, and the main meal we ate—a heavily calorific affair that was supposed to demonstrate how well-nourished the detainees were—was made even more inedible by the way that water (with the option of a can of Sprite) flowed like wine. Yet a few days later I ran into a friend at the White House who told me half-admiringly: “Way to go at Guantánamo: they say you managed to get your own bottle and open it down on the beach and have a party.” This would have been utterly unfeasible in that bizarre Cuban enclave, half-madrassa and half-stockade, but it was still completely and willingly believed. Publicity means that actions are judged by reputations and not the other way about: I never wonder how it happens that mythical figures in religious history come to have fantastic rumors credited to their names.

“Hitch: making rules about drinking can be the sign of an alcoholic,” as Martin Amis once teasingly said to me. (Adorno would have savored that, as well.) Of course, watching the clock for the start-time is probably a bad sign, but here are some simple pieces of advice for the young. Don’t drink on an empty stomach: the main point of the refreshment is the enhancement of food. Don’t drink if you have the blues: it’s a junk cure. Drink when you are in a good mood. Cheap booze is a false economy. It’s not true that you shouldn’t drink alone: these can be the happiest glasses you ever drain. Hangovers are another bad sign, and you should not expect to be believed if you take refuge in saying you can’t properly remember last night. (If you really don’t remember, that’s an even worse sign.) Avoid all narcotics: these make you more boring rather than less and are not designed—as are the grape and the grain—to enliven company. Be careful about up-grading too far to single malt Scotch: when you are voyaging in rough countries it won’t be easily available. Never even think about driving a car if you have taken a drop. It’s much worse to see a woman drunk than a man: I don’t know quite why this is true but it just is. Don’t ever be responsible for it.

Buy Hitch-22.

Christopher Hitchens on the Pope @ Slate.com April 12, 2010 April 25, 2010

Posted by rationalskeptic in Christopher Hitchens.Tags: Catholicism, Christopher Hitchens, Pedophilia, Pope

2 comments

Here is Christopher Hitchens’ most recent article on the rape, torture, and cover up committed by the Catholic church and the Pope. I thought it would be appropriate to post this article, considering the ratcheting up of pressure on the church in recent days:

We Can’t Let the Pope Decide Who’s a Criminal

Bringing priestly offenders and the church’s enablers to justice.

Posted Monday, April 12, 2010, at 10:47 AM ET

In 2002, according to devout Catholic columnist Ross Douthat, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger spoke the following words to an audience in Spain:

I am personally convinced that the constant presence in the press of the sins of Catholic priests, especially in the United States, is a planned campaign … to discredit the church.

On April 10, the New York Times—the apparent center of this “planned campaign”—reprinted a copy of a letter personally signed by Ratzinger in 1985. The letter urged lenience in the case of the Rev. Stephen Kiesle, who had tied up and sexually tormented two small boys on church property in California. Kiesle’s superiors had written to Ratzinger’s office in Rome, beseeching him to remove the criminal from the priesthood. The man who is now his holiness the pope was full of urgent moral advice in response. “The good of the Universal Church,” he wrote, should be uppermost in the mind. It should be understood that “particularly regarding the young age” of Father Kiesle, there might be great “detriment” caused “within the community of Christ’s faithful” if he were to be removed. The good father was then aged 38. His victims—not that their tender ages of 11 and 13 seem to have mattered—were children. In the ensuing decades, Kiesle went on to ruin the lives of several more children and was finally jailed by the secular authorities on a felony molestation charge in 2004. All this might have been avoided if he had been handed over to justice right away and if the Oakland diocese had called the police rather than written to the office in Rome where it was Ratzinger’s job to muffle and suppress such distressing questions.

Contrast this to the even more appalling case of the school for deaf children in Wisconsin where the Rev. Lawrence Murphy was allowed unhindered access to more than 200 unusually defenseless victims. Again the same pattern: repeated petitions from the local diocese to have the criminal “unfrocked” (an odd term when you think about it) met with stony indifference from Ratzinger’s tightly run bureaucracy. Finally a begging letter to Ratzinger from the filthy Father Murphy himself, complaining of the frailty of his health and begging to be buried with full priestly honors, in his frock. Which he was. At last, a human plea not falling on deaf ears! (You should pardon the expression.) So in one case a child rapist escaped judgment and became an enabled reoffender because he was too young. In the next, a child rapist was sheltered after a career of sex torture of disabled children because he was too old! Such compassion. It must be noted, also, that all the letters from diocese to Ratzinger and from Ratzinger to diocese were concerned only with one question: Can this hurt Holy Mother Church? It was as if the children were irrelevant or inconvenient (as with the case of the raped boys in Ireland forced to sign confidentiality agreements by the man who is still the country’s cardinal). Note, next, that there was a written, enforced, and consistent policy of avoiding contact with the law. And note, finally, that there was a preconceived Ratzinger propaganda program of blaming the press if any of the criminal conduct or obstruction of justice ever became known. The obscene culmination of this occurred on Good Friday, when the pope sat through a sermon delivered by an underling in which the exposure of his church’s crimes was likened to persecution and even—this was a gorgeous detail—to the pogroms against the Jews. I have never before been accused of taking part in a pogrom or lynching, let alone joining a mob that is led by raped deaf children, but I’m proud to take part in this one. The keyword is Law. Ever since the church gave refuge to Cardinal Bernard Law of Boston to spare him the inconvenience of answering questions under oath, it has invited the metastasis of this horror. And now the tumor has turned up just where you might have expected—moving from the bosom to the very head of the church. And by what power or right is the fugitive cardinal shielded? Only by the original agreement between Benito Mussolini and the papacy that created the pseudo-state of Vatican City in the Lateran Pact of 1929, Europe’s last remaining monument to the triumph of Fascism. This would be bad enough, except that Ratzinger himself is now exposed as being personally as well as institutionally responsible for obstructing justice and protecting and enabling pederasts. One should not blame only the church here. Where was American law enforcement during the decades when children were prey? Where was international law while the Vatican became a place of asylum and a source of protection for those who licensed or carried out the predation? Page through any of the reports of child-rape and torture from Ireland, Australia, the United States, Germany—and be aware that there is much worse to come. Where is it written that the Roman Catholic Church is the judge in its own case? Above or beyond the law? Able to use private courts? Allowed to use funds donated by the faithful to pay hush money to the victims or their families? There are two choices. We can swallow the shame, roll up the First Amendment, and just admit that certain heinous crimes against innocent citizens are private business or are not crimes if they are committed by priests and excused by popes. Or perhaps we can shake off the awful complicity that reports this ongoing crime as a “problem” for the church and not as an outrage to the victims and to the judicial system. Isn’t there one district attorney or state attorney general in America who can decide to represent the children? Nobody in Eric Holder’s vaunted department of no-immunity justice? If not, then other citizens will have to approach the bench. In London, as already reported by the Sunday Times and the Press Association, some experienced human-rights lawyers will be challenging Ratzinger’s right to land in Britain with immunity in September. If he gets away with it, then he gets away with it, and the faithful can be proud of their supreme leader. But this we can promise, now that his own signature has been found on Father Kiesle’s permission to rape: There will be only one subject of conversation until Ratzinger calls off his visit, and only one subject if he decides to try to go through with it. In either event, he will be remembered for only one thing long after he is dead. Become a fan of Slate on Facebook. Follow Slate and the Slate Foreign Desk on Twitter. Christopher Hitchens is a columnist for Vanity Fair and the Roger S. Mertz media fellow at the Hoover Institution.

Article URL: http://www.slate.com/id/2250557/ Copyright 2010 Washingtonpost.Newsweek Interactive Co. LLC

Submit a get well message to Christopher Hitchens.

Submit a get well message to Christopher Hitchens.